Published on November 29, 2019

Eastern’s Biology Department had a strong showing at the recent Waterbird Society meeting in Maryland this past November. Professor Patricia Szczys gave the opening plenary lecture and biology students Rachael Finch and Brittany Velikaneye presented on two aspects of an endangered migratory seabird common in the Northeast.

The 43rd annual meeting occurred from Nov. 6–9 at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, and featured presenters from 15 countries who gave more than 120 talks and 40 poster presentations.

The meeting opened with a lecture from Szczys, who was recently named vice president-elect of the Waterbird Society (effective Jan. 1, 2020) after serving as secretary for 12 years. Titled “Natural History and Genetics: Informing Tern Conservation and Undergraduate Research,” her presentation focused on collaborating with undergraduate students on professional research.

“My intention was to engage the graduate students and post-docs in attendance in a conversation about a career at a liberal arts college,” she said of her 50-minute lecture, “and how undergraduates can be meaningfully involved in faculty scholarship.”

“Primarily undergraduate academic institutions and small colleges following the tradition of the liberal arts typically shift the focus of faculty away from extensive grant-seeking and high-frequency, high-profile publication toward research-informed teaching and undergraduate-oriented research programs,” she wrote in her abstract. This, she says, is a model “from which students develop the ‘soft skills’ of critical thinking, problem solving and writing while maintaining the expectation of high-quality faculty scholarship.”

She highlighted a recent study conducted in partnership with former Eastern student Jacob Dayton ’19 that was recently submitted for publication, titled “Metapopulation Structure and Historical Population Size in the Northwest Atlantic Roseate Tern Population.” Dayton is amid his first semester as a Ph.D. student at Tufts University.

Her abstract explains: “Using this project as a case study, I demonstrate how one research program has taken practical approaches to deeply engage undergraduates in the classroom, in a molecular lab without graduate students and post-docs, and in intensive field experiences, all within the constraints of a significant teaching load.”

In the days following Szczys’ lecture, two of her students presented faculty-supported projects on terns—Szczys’ expertise and research interest.

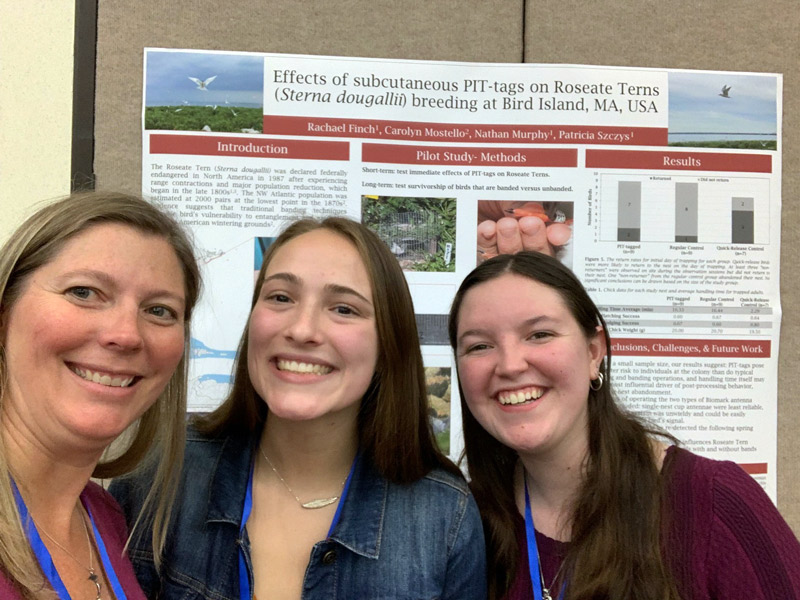

Finch ’22, a biology major, presented the results of her intensive field work conducted this past summer, titled “Effects of Subcutaneous PIT-Tags on Roseate Terns Breeding at Bird Island, MA, USA.”

“Roseate Terns are an endangered coastal seabird intensively studied in the Northeast Atlantic for more than 30 years,” she writes in her abstract. “Many Roseates in the population are banded (around the leg); however, observations

suggest that these bands cause mortality due to vulnerability of entanglement and by increasing their visibility and desirability to hunters in their South American wintering area.”

She said of the conference: “The best part was meeting people from all over the world, everyone at different stages in their lives and careers, sharing the same common goal of enlightening others with our research.”

Biology and psychology double-major Velikaneye ’20 presented on her honors thesis, titled “Microsatellites Can Exclude Paternity in Male-Female Pairs and Assign Maternity in Female-Female Pairs of Roseate Terns.”

Szczys noted that Velikaneye’s presentation was made to a crowded room of specialists, directly preceding a talk by a foundational figure in the field/society whose work encompasses nearly 60 years of work on terns—the back-to-back presentations given by possibly the meeting’s youngest and oldest attendees.

“Prior to the application of molecular genetic tools to mating system studies in birds, it was commonly assumed that almost all were both socially and sexually monogamous,” her abstract reads. “However, the molecular data has often refuted this common belief as only a small percentage of species are now considered strictly sexually monogamous.”

Szczys has made a career of mentoring undergraduate students such as Finch and Velikaneye, and nurturing them to become professional researchers via the study of terns. Her lab has exposed numerous students to important issues in tern evolution and conservation as they complete multi-year research projects.

As the new vice president-elect of the Waterbird Society, she said of Roseate terns: “Because they are protected under the Endangered Species Act, we need to learn as much about the causes and consequences of population declines so that we can try to manage the problems and improve future outcomes.

“My research aims to inform management,” said Szczys, adding, “I just love these birds—so much already learned and so much yet to learn!”

The Waterbird Society is an international scientific, not-for-profit organization whose mission is to foster the study, management and conservation of the world’s aquatic birds. The society’s primary goals are to promote research on waterbirds and their habitats; foster science-based waterbird conservation; and enhance communication and education among professional, policy makers and citizens

Written by Michael Rouleau