- Apply

- Visit

- Request Info

- Give

Published on November 03, 2020

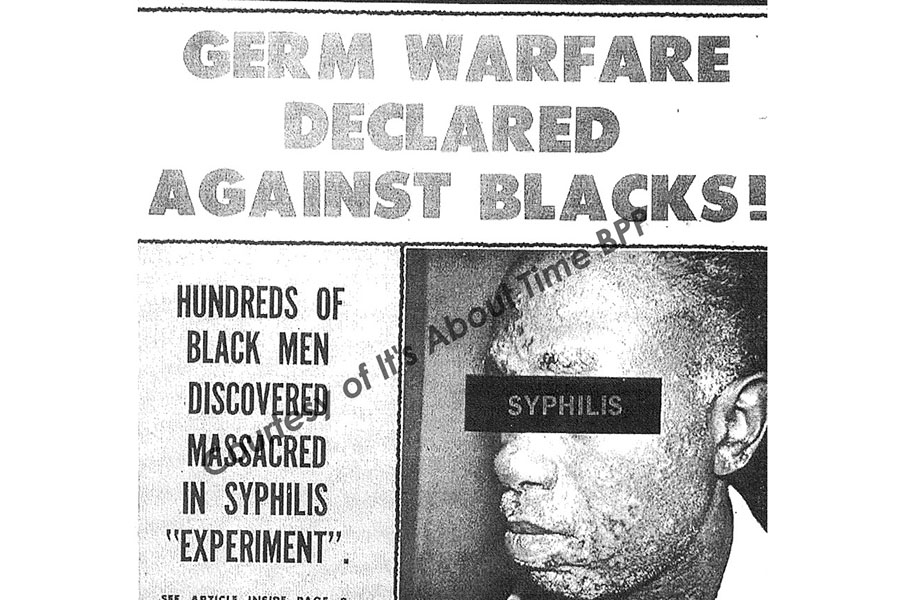

In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service engaged in an experimental study designed to determine the natural course of untreated, deadly syphilis in 400 African American men in Tuskegee, AL. Dr. Peter Millet, executive vice president at Meharry Medical College, called the study “the most unethical research and social injustice in the nation’s history” during a virtual seminar on Oct. 28 at Eastern Connecticut State University.

In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service engaged in an experimental study designed to determine the natural course of untreated, deadly syphilis in 400 African American men in Tuskegee, AL. Dr. Peter Millet, executive vice president at Meharry Medical College, called the study “the most unethical research and social injustice in the nation’s history” during a virtual seminar on Oct. 28 at Eastern Connecticut State University.

Millet said as far back as the days of slavery, African Americans have been used as subjects for a variety of surgical demonstrations, even without anesthesia. As a result, Millet said the Tuskegee Syphilis Study — 88 years later — lies at the bottom of African American reservations about testing for the COVID-19 vaccine.

Millet said as far back as the days of slavery, African Americans have been used as subjects for a variety of surgical demonstrations, even without anesthesia. As a result, Millet said the Tuskegee Syphilis Study — 88 years later — lies at the bottom of African American reservations about testing for the COVID-19 vaccine.

Millet said that in the study, African American men were injected with the virus that causes syphilis and were matched against 200 uninfected subjects who served as a control group. Doctors then deceived the men into believing they were being treated for so-called “bad blood.” Millet said it was obvious that the doctors, aware of the availability of penicillin to treat syphilis, knew exactly what they were doing.

In 1972, when the national press exposed the unethical treatment of the victims of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare ended the experiment. In 1974, the U.S. government reached a $10-million-dollar settlement and promised to give lifetime medical benefits and burial services to all living participants.

But the damage was done. More than 100 men died. In the early ’90s, the courts ordered an average $40,000 award to the survivors. President Bill Clinton apologized to the remaining survivors in 1997.

Millet, a clinical psychologist and former president of Stillman College, linked this ugly event in American health history to current low levels of African American research participation during COVID-19. Additionally, he believes that apparent health disparities between African Americans and White Americans are correlated to the incidence of COVID-19.

Millet said structural, conceptual and educational barriers must be crossed before new studies can be conducted among African Americans. “The Center for Disease Control says minorities are underrepresented in COVID-19 trials and are the hardest hit by COVID-19. Clinical trials are considered the gold standard of medical treatment today. Most trials must include minorities and women to secure federal funding. We’ve got to trust education more. By abstaining from trials, African Americans hurt themselves, as drug companies can better analyze subgroups.”

Millet concluded his presentation by citing prominent African American doctors who are volunteering to participate in COVID-19 trials. He encouraged the audience to tell potential research participants or subjects to do the same.

Millet concluded his presentation by citing prominent African American doctors who are volunteering to participate in COVID-19 trials. He encouraged the audience to tell potential research participants or subjects to do the same.

The event was sponsored by the Office of Equity and Diversity, Department of Education, the Diversity and Social Justice Council, Office of Housing and Residential Life, Arthur L. Johnson Unity Wing and the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Criminology and Social Work.

Written by Dwight Bachman